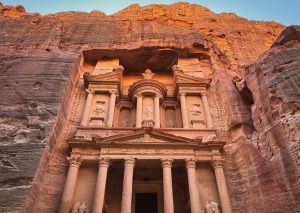

Sainte-Cecile Cathedral in Albi is famously the largest brick cathedral in the world. It has towered over the city like a fortified castle for the last 545 years. On my recent trip to Toulouse, I hopped on the train so I could look within its formidable pink walls.

Albi doesn’t hit you like Paris or Rome. It creeps up on you, a quiet and small city in southern France where the Tarn River bends lazily, and then – bam – the cathedral rises out of the brick like it’s gearing up to take revenge on a sworn enemy. At least that’s how I imagine it must look on a dark and gloomy day. Thankfully, the sun was shining and it looked more like a gigantic Madeleine cake, albeit not quite as spongy.

Sainte-Cecile Cathedral isn’t your standard Gothic confection. Forget delicate spires and lots of lacy stonework. This thing is a fortress, a statement, built out of red brick by men who wanted to make sure you knew who was boss.

A brief history of Sainte-Cecile Cathedral

Construction began in 1282 under the order of Bishop Bernard de Castanet. It came in the aftermath of the Albigensian Crusade, when the Catholic Church crushed the Cathars, a local religious movement that dared to question Rome’s authority. Built entirely of brick — unusual for Gothic cathedrals — its fortress-like appearance wasn’t just aesthetic. It was a statement: the Church was in charge, and resistance was futile.

Over the next two centuries, the cathedral rose above the Tarn River valley, with its massive walls, single nave, and imposing bell tower. If you thought the outside was impressive, wait until you see inside.

By the time it was consecrated in 1480, Sainte-Cecile was not only a place of worship but also a monument to Catholic victory, civic pride, and artistic ambition. From the 15th to 16th centuries, the interior was filled with flamboyant Gothic decoration, Renaissance frescoes, and an elaborate rood screen separating clergy from the laity, otherwise known as ordinary folk.

Today, it’s recognised as the largest brick cathedral in the world and part of Albi’s UNESCO World Heritage designation. It stands as both a masterpiece of medieval architecture and a historical reminder of how faith and power were once inseparable.

I’ve been to many cathedrals all over the world, but this one really does set itself apart in many ways. It’s sort of intimidating, actually. I mean, even some of the statues inside are depicted with bulging biceps and rippling torsos that would make prime Arnold Schwarzenegger look kind of soft in comparison. Maybe a better comparison would be the statues of men depicted in Greek mythology – on steroids. Whatever the reason, I found a cathedral to be an unlikely home for these exaggerated depictions of the human form.

The Last Judgment fresco

The most famous fresco is the vast Last Judgment, painted around 1474 by Flemish artists. I wish I had zoomed in on specific segments to showcase the insane details. If you’re familiar with work by Bosch or Bruegel – it’s very much reminiscent of their works.

The fresco is one of the largest of its kind in the world, designed to terrify sinners into obedience. At one point I even started questioning my past behaviour and wondered whether I should make a trip to confession now that I was here.

The vaults are painted in an otherworldly sea of blues and golds, an explosion of colour that feels almost defiant against the monotone exterior. The Last Judgment fresco, covering the west wall, is a medieval horror show — devils torturing sinners, grotesque creatures dragging the damned into hellfire. It’s brutal, visceral, and not remotely subtle. With depictions like this, I would never have dared step a foot out of line back in the day.

The vault frescoes

If the Last Judgement was made to scare, the vault frescoes were designed to inspire. The ceiling sings with delicate patterns and heavenly imagery, like the builders and artists knew they had to balance out the mood.

You have to tilt your head far back to get the full scene. High above, the entire ceiling glows in a deep ultramarine blue, painted with scenes of heaven, angels, and saints. The pigments came from lapis lazuli imported from Afghanistan, a luxury that announced both wealth and devotion. No expense spared.

The choir

The choir is another world entirely. Carved wooden stalls, filigree stone screens, and statues so intricate you half expect them to start whispering secrets. The word sublime comes to mind.

It’s some of the most intricate displays of stone craftsmanship I’ve seen in any place of worship. Now is a good time to mention that the cathedral is dedicated to Saint Cecilia the patron saint of musicians and yes, choirs. It’s no wonder so much attention was appointed to this part of the cathedral.

I wasn’t fortunate to witness, or rather hear, a choral concert underway during my visit, so I can only imagine the heavenly sound of high notes soaring to the vaulted ceilings like white-winged doves.

The treasury rooms

Upstairs in the treasury, you’re suddenly face to face with objects that once carried immense spiritual and political weight. Illuminated books of hours, psalters, and choir books, with gilded initials and intricate marginalia that once guided the prayers of monks and bishops. There are also liturgical Objects such as chalices, monstrances, and censers, many crafted in precious metals and adorned with jewels, reflecting the craftsmanship of the period.

The piece that caught be attention was a bejewelled cross, known as a reliquary cross. This is a Christian cross-shaped object designed to hold religious relics, often associated with the crucifixion of Christ. Placed inside the middle of the crystal is a teeny tiny wooden cross.

Note: Entrance to Albi Cathedral is free, but access to the Treasury and the choir requires a ticket that you can purchase inside.

Palais de la Berbie

There’s also the adjoining Palais de la Berbie, once the bishop’s palace, now home to the Toulouse-Lautrec Museum. Few other artists are more ubiquitous with the image of Paris than Lautrec. The short, sharp-eyed painter who immortalised the decadence of Montmartre. Well, he was born in Albi.

His art feels like a sly wink from the city that built the most intimidating cathedral in Europe: life isn’t all fire and brimstone. There’s also beauty, laughter, and maybe a few bad decisions after too much wine.

Final thoughts

Albi Cathedral is a paradox. Brutal on the outside, breathtaking within. It tells you everything about medieval France – faith and fear, power and art, damnation and salvation – and maybe something about us too. While I wouldn’t call myself religious I’m still drawn to places that make us feel small. That make us reflect. Sainte-Cecile Cathedral reminds us of the weight of history, and the human need to leave something behind that says: we were here, and we created what you see now.

Is it worth going out of your way to see while travelling around France? Yes, absolutely. See what other attractions you can visit with my guide to Albi.